Josef Hoffmann's Vienna

January 21–April 3, 2022

Presented by Deputy Curator Christopher Herron, chosen from the collection assembled by Founding Director & Curator Hugh Grant

Temporary Exhibition Gallery 12

Welcome to Austria!

Imagine yourself strolling along the streets of Vienna and hearing strains of Mahler playing from the beautifully decorated cafés. This is the place that Josef Hoffmann loved, the place where he would become a trailblazer for architecture and design in the 20th century.

From 1850 to 1910, Vienna’s population grew from 500,000 residents to over two million. The Viennese were embracing new technologies with the installation of streetlights and an electric tram. In this season of rapid change, young artists found themselves swept up in a belief in progress and the desire to bring a new and modern art to Vienna.

Josef Hoffmann’s Vienna, designed to delve deeper into an important part of Kirkland Museum’s permanent collection, explores Hoffmann’s immense impact on Vienna and the western world during the early 20th century. As you journey through the exhibition, you will discover objects that demonstrate Hoffmann’s roles in the Vienna Secession, their publication, Ver Sacrum, and the subsequent Wiener Werkstätte (“Vienna Workshops”). Stop by the Cabaret Fledermaus for a show and imagine sipping a coffee (or perhaps something a little stronger) in this cohesive and elegantly-designed space.

All decorative art pieces in the exhibition were designed by Josef Hoffmann.

Exhibition Music

Listen anytime to our exhibition playlist of Viennese cabaret music, curated by Founding Director & Curator

Hugh Grant, below and available on Spotify.

Josef Hoffmann (1870–1956)

Josef Hoffmann was an architect and is also well-known today for designing over 1000 pieces of furniture and other objects. Hoffmann was partly responsible for creating a new style and identity for Vienna in the early 20th century. This bold new aesthetic relied heavily on geometry instead of the curving, sinuous Art Nouveau designs popular in France and Britain. The square dominated Hoffmann’s early career, earning him the nickname Quadratl Hoffmann (“Square Hoffmann”).

Vienna Secession

“We [the Secessionists] do not recognize any difference between great and minor art, between the art of the rich and that of the poor. Art belongs to all.” —Ver Sacrum, 1897

The Vienna Secession was formed in 1897 when a group of young artists and architects broke away from the conservative Viennese artists’ association, which they saw as too traditional and rooted in the past.

A few years before the founding of the Vienna Secession, two separate groups of artists began meeting in coffee houses to discuss art and politics. Those two groups were the Siebener Klub (“Club of Seven”) and the Hagenbund (named after the owner of their favorite café). Members of these groups merged and became the Secessionists, each rejecting the imitation of past styles and embracing the new and the modern.

There was no agreed upon singular style for the Secession artists, but two of its leading designers, Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser (1868–1918), were responsible for the geometric, linear and repeated motifs that were wildly popular at the time. These symbols became the style language of the Secession.

The group began by building their own exhibition hall in 1897–1898, designed by Josef Maria Olbrich (1867–1908), and printing a periodical titled Ver Sacrum to promote their philosophies.

In 1905, a dispute began between members of the Secession which led to Hoffmann, Gustav Klimt (1862–1918), Otto Wagner (1941–1918) and others leaving. They were known as the Klimt-Gruppe. With the Klimt-Group gone, the Secession continued to exhibit, but the creative output suffered.

Although Hoffmann was only part of the Secession for eight years, he and other artists ushered in a new and modern style that would take the Western world by storm.

Ver Sacrum

To bring the idealist message of the Vienna Secession to the public, the Secessionists created Ver Sacrum, a journal promoting their philosophies, art and design. Josef Hoffmann served on the editorial board for the first year of publication and would contribute artwork regularly. The title, Latin for “sacred spring,” was inspired by the season the Vienna Secession was founded and relates to their desire for a rebirth of their city.

The first issue was published in January 1898 and for the first two years, Ver Sacrum was published monthly. The journal featured lithographs, woodcuts, illustrations, poems and essays by artists of the Secession in editions of about 400-500 copies each. During the years of publication, 120 issues were printed. The first 11 issues, while Hoffmann served on the editorial board, are exhibited here.

Each journal was formulated like a small exhibition and most issues focused on the work of one artist. Each issue therefore was an example of Gesamtkunstwerk (“total work of art”).

Ver Sacrum is recognized for its advances in graphic design, typography and illustration, setting an example for later art magazines. Notice the square format—Vienna’s, and specifically Hoffmann’s, favorite symbol of modernity.

Ver Sacrum ceased publication in 1903, the same year the Wiener Werkstätte was formed and two years before the Secession fractured. The cost of producing the journal had become too great and fissures in the group led to the publication’s demise.

What is Gesamtkunstwerk?

This German word roughly translates to “total work of art”—a combination of various artistic elements to create a cohesive whole.

In an architectural context, this means the architect is responsible for the design of the whole project, including the building, furnishings, decorative designs and landscape. This was a guiding principle for many architects, including Josef Hoffmann and his contemporary, Frank Lloyd Wright.

Flip through the first issue of Ver Sacrum, 1898:

Wiener Werkstätte

The Wiener Werkstätte (“Vienna Workshops”) were founded in 1903 as a business collaboration between Josef Hoffmann, designer Koloman Moser and wealthy industrialist and art patron Fritz Waerndorfer. The Werkstätte originated as a decorative art studio creating modern designs with impeccable craftsmanship inspired by the guild model of the British Arts & Crafts Movement.

Hoffmann and Moser had three goals:

establish a direct relationship between designer, craftspeople and the public

create a style reflecting the “spirit of their own time”

promote functional objects as equal to painting and sculpture

The Werkstätte had no strict design style, but often produced simple patterns and geometric designs, like Hoffmann’s black and white checkerboard motif. Hoffmann and Moser’s use of the grid pattern and right angles, also seen in Glasgow Style, are considered some of the earliest examples of abstraction. Vienna was among the most important places for the birth of modernism, alongside Paris and Berlin.

Hoffmann left the Wiener Werkstätte in 1931. The next year the Werkstätte was forced to close due to financial hardship in the wake of World War I and the American stock market crash, ending a remarkably long and influential run. From 1903 to 1932, the Wiener Werkstätte created objects of immense creativity and beauty and brought forth ideas that would inspire the Bauhaus and Art Deco movements to come.

Cabaret Fledermaus

Fledermaus means “bat” in English, or literally “flutter mouse”

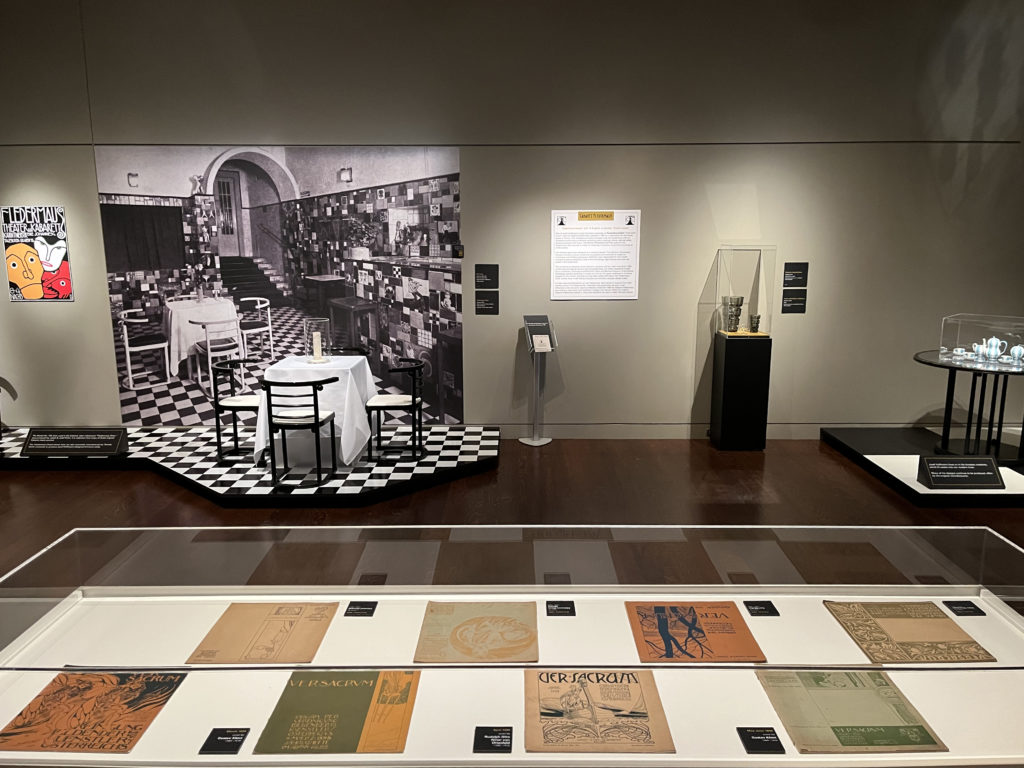

From Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, vol. 23, 1908. Image Courtesy of Neue Galerie, New York

One of Josef Hoffmann’s most important examples of Gesamtkunstwerk (“total work of art”) was the Cabaret Fledermaus, opened in 1907 as a destination for the avant-garde of Vienna. The underground space included a bar and auditorium with an ambitious performance schedule including poetry readings, dance, satirical plays, shadow puppetry and music. The Wiener Werkstätte had lofty goals for the Fledermaus; they wanted to create an inspiring, immersive experience involving all of the senses.

The finished space was designed as a cohesive whole. The interiors, dinnerware, fixtures, furniture, menus, costumes and graphics all combined to create an immersive and thrilling experience. Hoffmann was responsible for the overall concept as well as designing most of the furnishings, light fixtures and even the carpet in the auditorium.

The architectural detailing of the Cabaret’s entrance and bar used more than 7,000 colorful flat and figural ceramic tiles alongside black and white checkered marble floors. Hoffmann commissioned Berthold Löffler and Michael Powolny of the Wiener Werkstätte ceramic workshop to create the tiles for the space. Hoffmann’s furniture designs for the interior included serving trays, chairs and tables. His Fledermaus Chair is still being produced and remains a popular design today.

For two years the Werkstätte ran the Fledermaus, with hands-on support from their wealthy patron Fritz Waerndorfer. Ultimately this experiment, though it was influential in the art world, wasn’t profitable. In October 1909 the Cabaret Fledermaus was sold to a new owner and Hoffmann’s design was altered. While the original Cabaret Fledermaus closed in 1913, new iterations are open in New York and Vienna.

Hoffmann’s Legacy

Josef Hoffmann lives on in his timeless creations, which fit neatly into our modern lives. Many of his designs continue to be produced, often by the original manufacturers.

Wiener Werkstätte designs are always on view at Kirkland Museum in Art Nouveau Gallery 4, where they can be compared with Art Nouveau and Glasgow Style designs from the same era.

What was the

Wiener Werkstätte?

Founded 1903.

Wanting to unite art with life, the Wiener Werkstätte embraced all creative disciplines and held many exhibitions. Architecture, fashion, painting, poetry, music, dance, graphics and decorative art were all valued.

Thank you to our sponsor:

Additional sponsorship opportunities are available. Email [email protected] to start the conversation.

Thank you to Patrick Greaney, Professor of German and Humanities, University of Colorado Boulder, for the pronunciation audio recordings.

Thank you to Jill A. Wiltse and H. Kirk Brown III for their gift supporting the exhibition display.