VIRTUAL EXHIBITION; In-person exhibition closed January 3, 2021

Curated by Christopher Herron

Kirkland Museum celebrated the March 2020 Month of Printmaking (Mo’Print)—and then extended the celebration through the end of 2020—by highlighting and explaining some of the processes and techniques used to create fine art prints, illustrated with examples by some of the great printmaking artists in Colorado history. The selected prints are all from the Museum’s permanent collection.

Deputy Curator Christopher Herron selected a group of prints by Colorado & regional artists that illustrate the wide variety of images possible in the art of printmaking. Original printing blocks and plates, study drawings and printing equipment are also on display. Not every printing process is included in this exhibition, and there are many variations of the four that we’re highlighting. Each of the four types of printmaking included are explained in detail below, followed by a slideshow of images from that section of the exhibition.

As part of the Kirkland’s mission of showcasing Colorado and regional art, Kirkland Museum Founding Director & Curator Hugh Grant continues to build on a collection of over 1000 prints spanning two centuries of work in a variety of media created by the state’s visiting and resident artists.

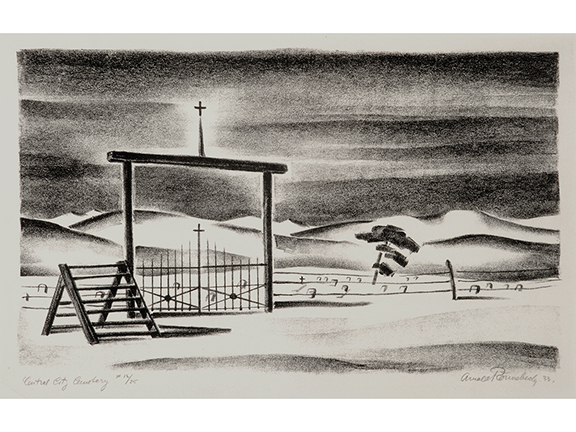

Lithography

Lithography is a planographic (flat surface) printing process based on the principle that grease and water do not mix. The traditional printing plate is limestone (Lithos is Greek for “stone”) but a flat plate of zinc or aluminum can also be used.

The image is created on the stone with oily marks, often drawn with a grease pencil known as a lithographic crayon. Chemical processes make these greasy crayon marks accept printing ink and repel water, and the unmarked stone receptive to water and resistant to grease. Oil-based ink is passed over the stone and sticks only to the greasy areas drawn on the stone. Paper is laid on the stone and pressed and a reverse image is transferred to the paper.

A different stone or printing plate is required for each color. The two Lawrence Barrett prints on view in this gallery demonstrate the variety of outcomes possible when using different drawing techniques and color to create mood.

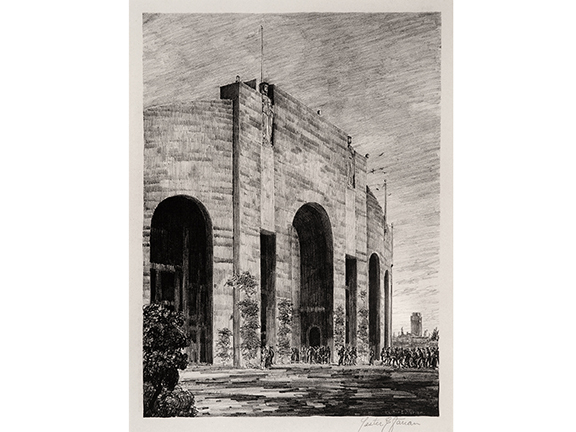

1933

lithograph, 12/25; crayon drawing study

Arnold Rönnebeck

(1885–1947, American, b. Germany)

Printed by Theodore Cuno, Philadelphia, PA. Cuno ran a business that produced prints for many nationally known artists.

1923

lithograph

C.A. Seward

(1884–1939, American)

Printed by master printers Fred Blume or Ernest W. Bullinger at Western Lithograph Company in Wichita, KS.

1930

lithograph, 28/40

Lester Varian

(1881–1967, American)

Printed by lithographers at the Bradford-Robinson Printing Company, founded 1881 in Denver, today known as Bradford Publishing.

1940 or earlier

lithograph

Lawrence Barrett

(1897–1973, American)

Printed by the artist at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center, where he was an instructor of etching and lithography from 1938 to 1952.

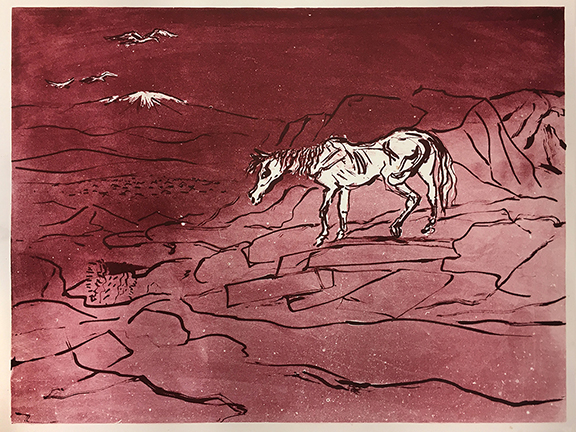

1940s

lithograph

Lawrence Barrett

(1897–1973, American)

Printed by the artist at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center, where he was an instructor of etching and lithography from 1938 to 1952.

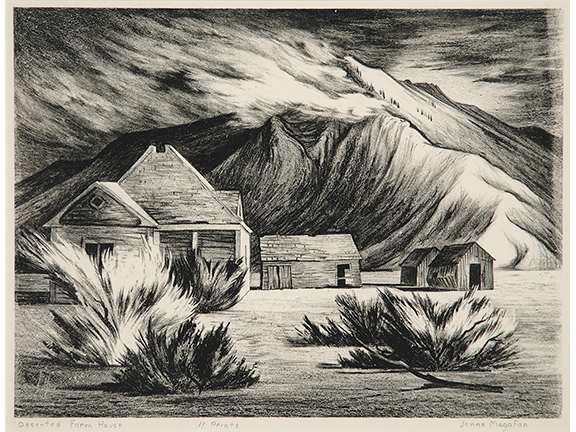

1941

lithograph, edition of 11

Jenne Magafan

(1916–1952, American)

Probably printed by Lawrence Barrett at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center.

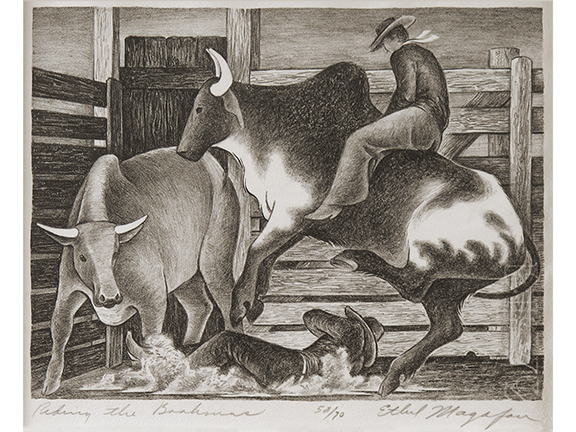

c. 1938

lithograph, 58/70

Ethel Magafan

(1916–1993, American)

Probably printed by Lawrence Barrett at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center.

1945

lithograph, edition of about 25

Frank Mechau

(1904–1946, American)

Probably printed by Lawrence Barrett at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center.

between 1932–1942

lithograph, 4/22

Harold Keeler

(1905–1968, American)

Printed by the artist, probably during his years living and working in Denver, 1932–1942.

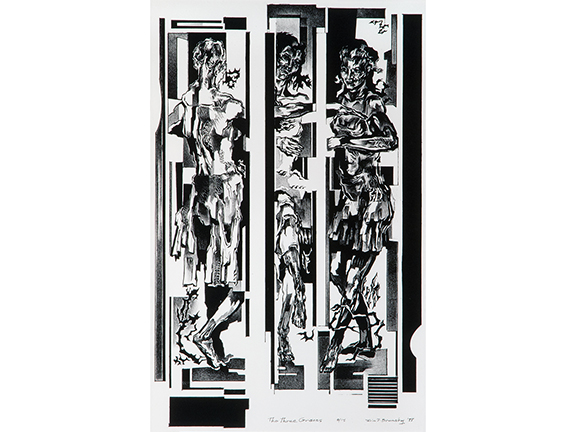

1977

lithograph, 8/14

Eric Bransby

(1916–2020, American)

Unknown printer. Bransby was teaching at the University of Missouri-Kansas City at the time (from 1965 to 1984).

1977

lithograph, 37/50

Beverly Rosen

(1924–2006, American)

Printed by the artist and Bud Shark at Shark’s Lithography Ltd., Boulder, CO (now Shark’s Ink in Lyons, CO).

1988

lithograph, 60/65

Betty Woodman

(1930–2018, American)

Printed by SOLO Impression, Inc., Bronx, NY. Woodman lived for a time in Boulder, CO, where she taught at the University of Colorado.

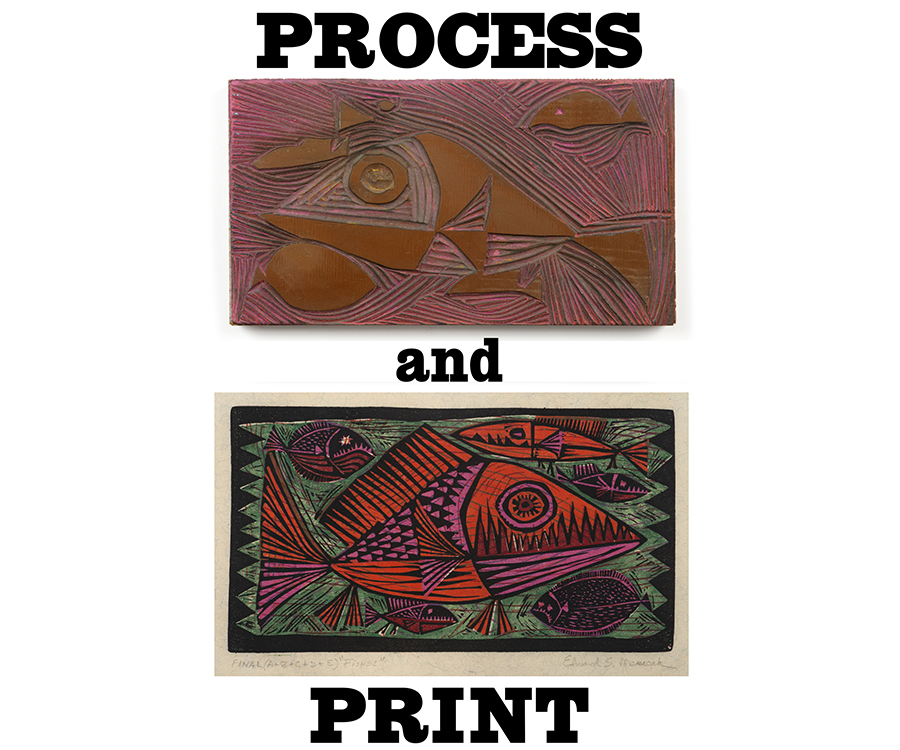

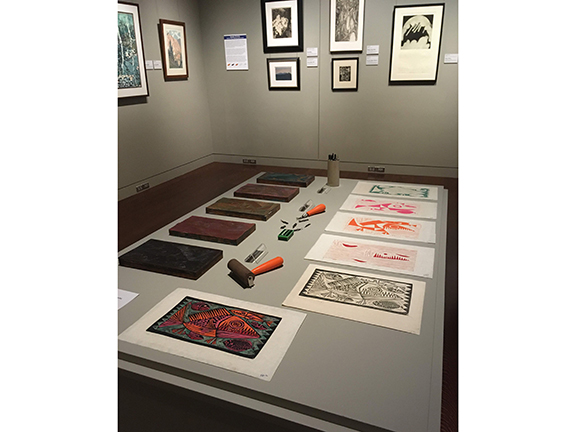

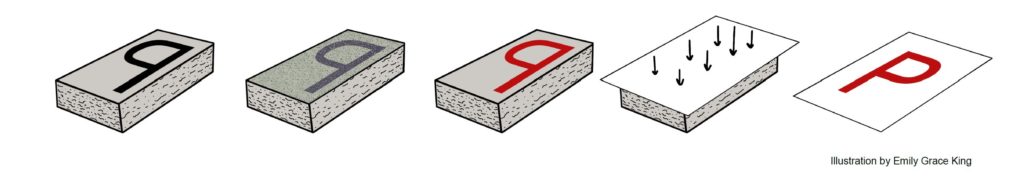

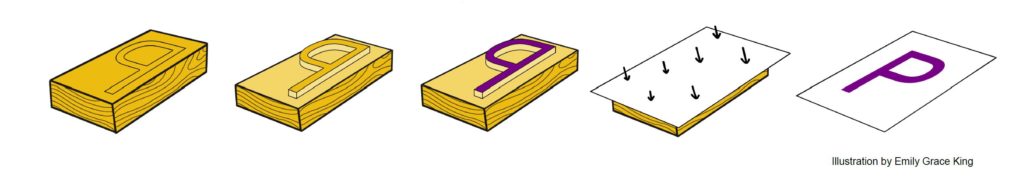

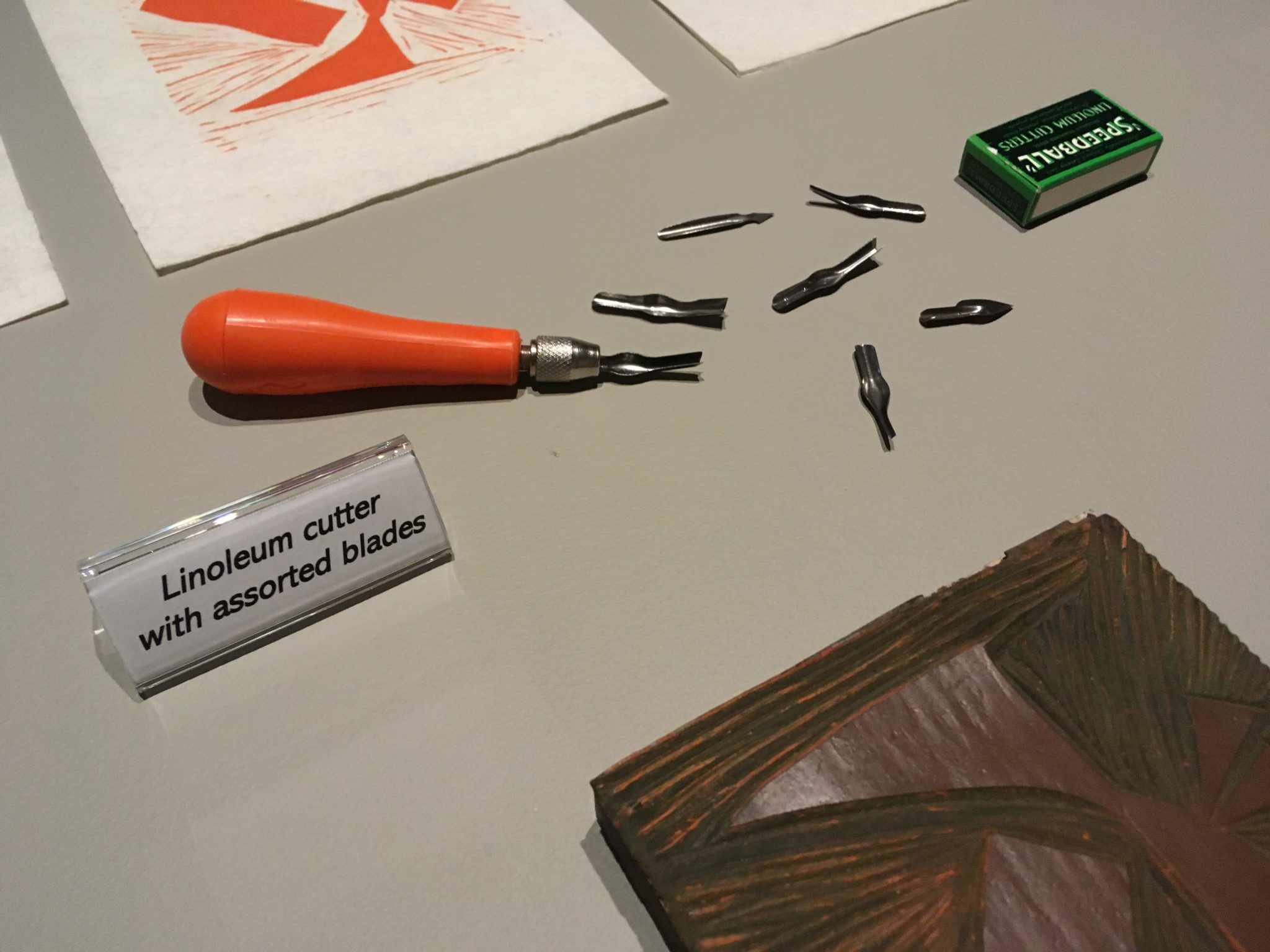

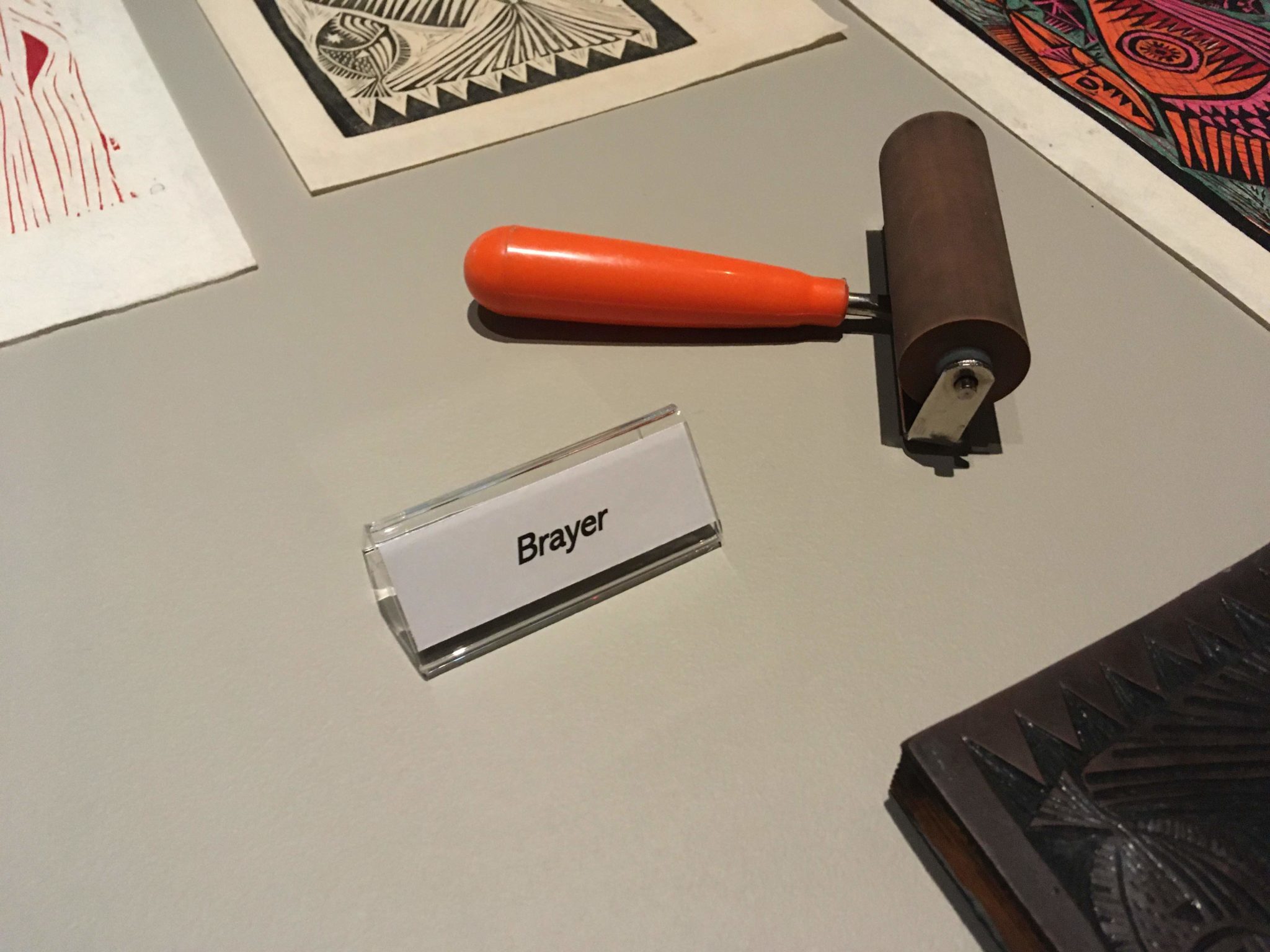

Relief Printing

Includes woodcut, linocut, wood engraving

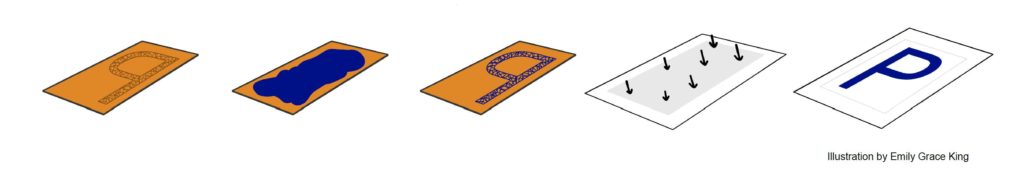

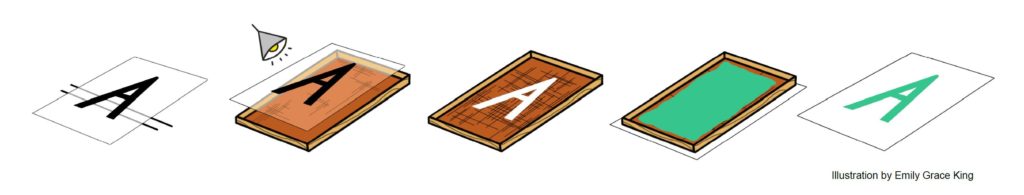

The printing block used for relief printing is commonly made from wood (creating a woodcut) or linoleum (a linocut). A knife or chisel is used to remove material from the non-printing areas and ink is applied with a roller to the remaining raised areas of the block. Paper is laid onto the block and under pressure the ink on the raised printing surface is transferred to the paper.

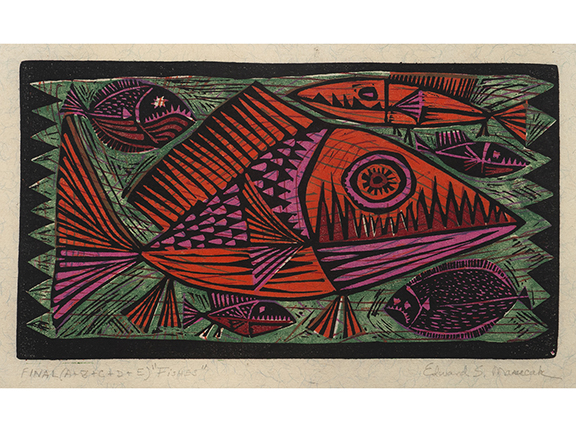

The resulting print is a reverse image of what is carved into the block. Prints can be multi-colored by using a separate block for each color (as with Edward Marecak’s Fish).

An alternative to multiple blocks is using a single block in the “reduction” method, in which the entire edition is printed one color at a time from light to dark, printing over the color below it. After each color is printed, the block is further carved (reduced) to form the surface for the next color. Because the block is carved away in the process, no further editions of this image are possible. The included prints by Jean Gumpper and Leon Loughridge are examples of this printmaking technique.

1918

woodcut, 6/100

Gustave Baumann

(1881–1971, American, b. Germany)

Printed by the artist. In 1918 Baumann moved from Indiana to Santa Fe, NM, and printed Indiana scenes in both places.

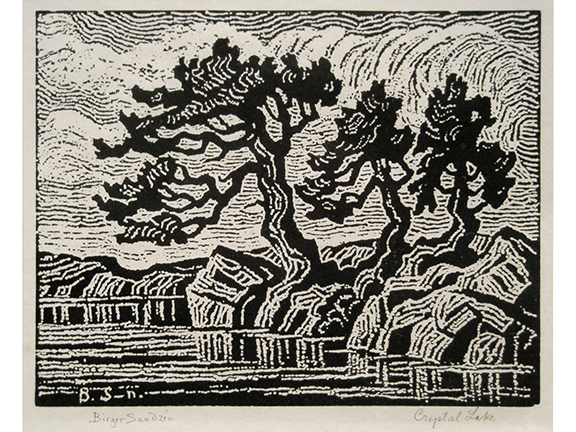

1928

woodcut (“nailcut”), 200 prints

Sandzén created the lines by repeatedly pounding a nail into the block.

Birger Sandzén

(1871–1954, American, b. Sweden)

Probably printed at the Lindsbourg News Record, Lindsbourg, KS. After his first block print in 1917,

Sandzén had others do his block printing for him.

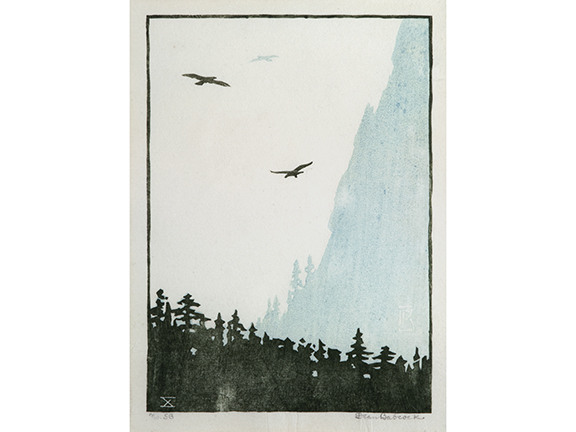

c. 1920

woodcut

Dean Babcock

(1888–1969, American)

Printed by the artist in his Estes Park, CO studio.

1950

woodcut

Cornelis Ruhtenberg

(1923–2008, American, b. Latvia)

Printed by the artist and Sid Stallings at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center.

Gift of Norm Anderson

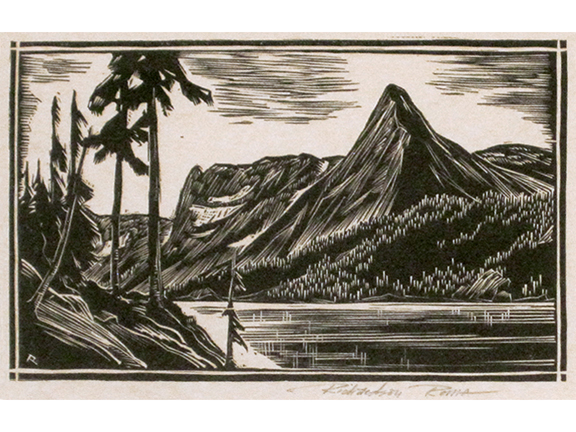

between 1931–1954

wood engraving

Richardson Rome

(1902–1981, American)

Printed by Rome Creations, the artist’s business in Estes Park, later Boulder and Denver, that produced stationery and postcards featuring original prints.

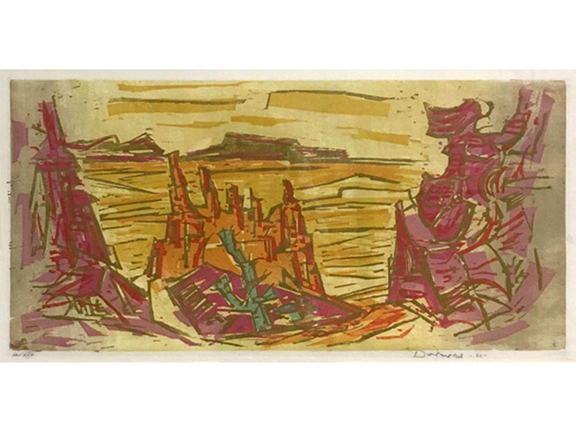

1962

woodcut, 12/30

Werner Drewes

(1899–1985, American, b. Germany)

Printed by the artist in St. Louis, MO. Drewes travelled throughout Colorado and the American Southwest while living and teaching in St. Louis.

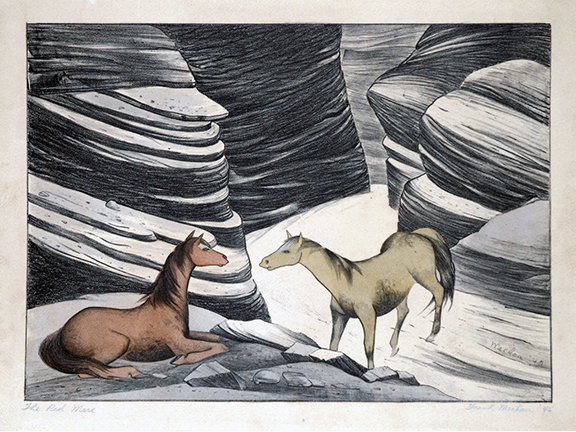

late 1960s

woodcut, 7/30

Dorothy Mandel

(1920–1995, American)

Printed by the artist in her Boulder, CO studio.

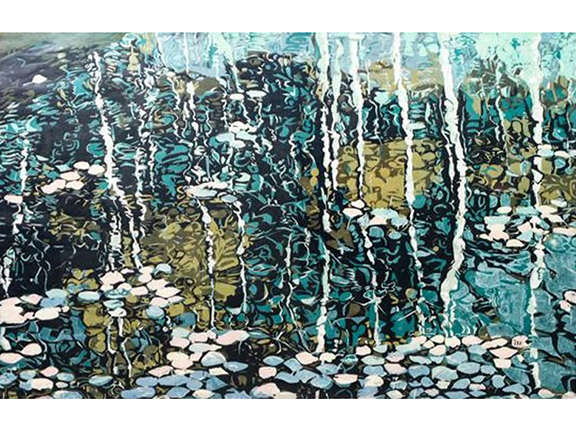

1970s

woodcut

Mary Chenoweth

(1918–1999, American)

Printed by the artist at Colorado College in Colorado Springs, where she taught art and printmaking from 1957 to 1983.

2004

reduction woodcut, 2/10

Jean Gumpper

(b. 1955, American)

Printed by the artist at Colorado College in Colorado Springs, where she is Lecturer and Artist in Residence.

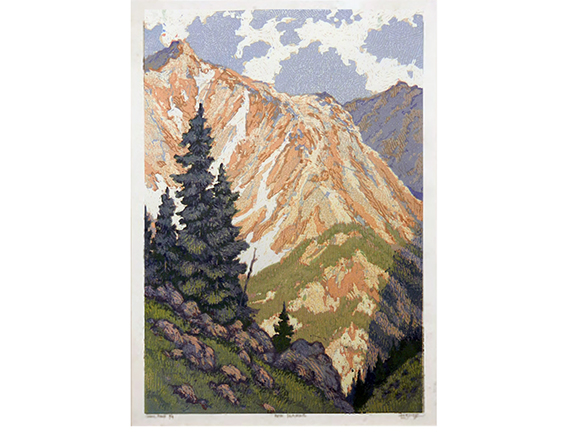

2014

reduction woodcut, Artist’s Proof 2/4

Leon Loughridge

(b. 1952, American)

Printed by the artist at Dry Creek Art Press, Denver.

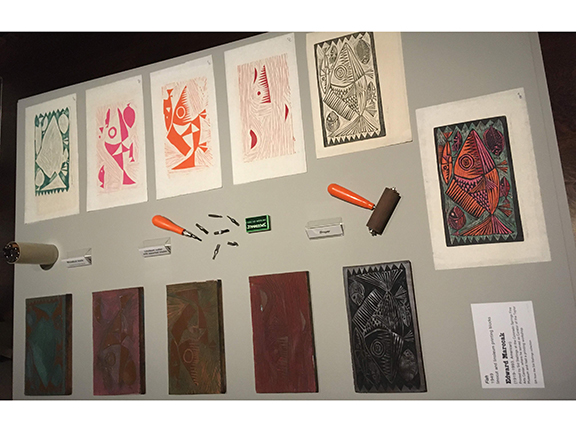

Fish

1949

linocut and linoleum printing blocks

Edward Marecak

(1919–1993, American)

Printed by Sid Stallings at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center, where he served as Curator of the Taylor Museum and had a printing workshop.

Gift from the Sid Stallings collection

1949

linocut

Edward Marecak

(1919–1993, American)

Printed by Sid Stallings at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center, where he served as Curator of the Taylor Museum and had a printing workshop.

Gift from the Sid Stallings collection

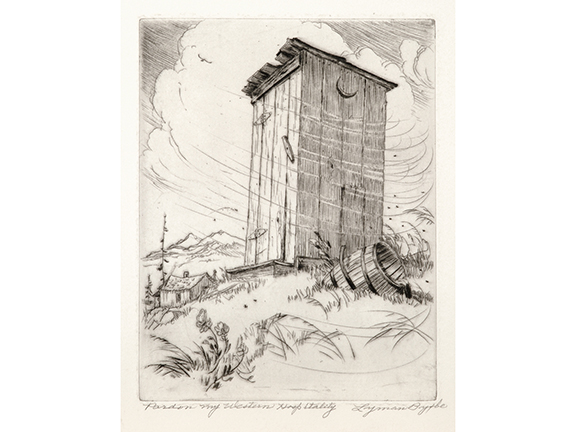

Intaglio Printing

Includes etching, engraving, drypoint, aquatint

Intaglio [in-tal-yoh] is Italian for incising or engraving. The image is cut into the surface of the plate, commonly copper or zinc, with a diamond-shaped cutting tool called a burin (for an engraving) or a sharpened needle (for a drypoint). Or, instead of cutting directly into the printing plate, the plate can be chemically etched by acid (creating an etching), which bites into the metal where it has been exposed through a protective acid-resistant ground.

During printing the ink collects in the valleys below the surface of the plate. To reach the bottom of these recesses and transfer all of the ink, greater pressure is required than with relief printing, and the paper is moistened to make it flexible. The damp paper is pressed around the edges of the plate during printing, leaving a telltale plate mark surrounding the image, a characteristic of an intaglio print.

An aquatint is made by spreading an acid-resistant ground over the plate which produces an area of overall tone or gradation when the plate is etched. Aquatint can be used on its own, or combined with etched lines as seen in the George Burr and Gene Kloss prints in this gallery, among others. All of these intaglio techniques can be combined on one plate to create a print, or a single technique may be used.

What is chine collé?

Chine collé [shin collay] is a French term for a process that introduces color and texture into a print by using pieces of paper added to a plate for printing. Paper for chine collé can be any type of lightweight paper but good quality, natural-fiber papers are most compatible. Chine collé papers are brushed with a coating of wheat paste (so they stick to the paper) and placed on top of the inked plate in their desired locations. The papers adhere to the print when run through a press. The colored shapes in the Mark Lunning print are chine collé."

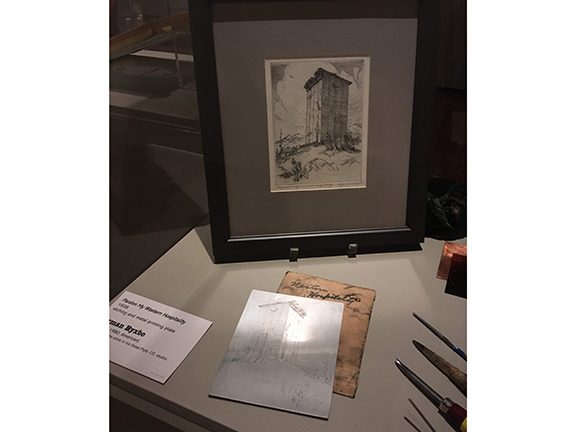

1938

etching

yman Byxbe

(1886–1980, American)

Printed by the artist in his Estes Park, CO, studio.

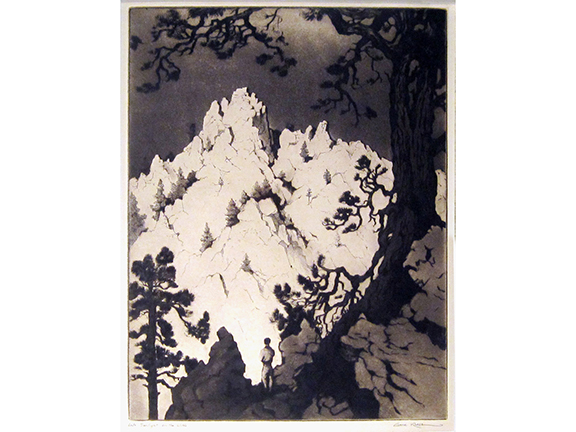

1941

etching, drypoint and aquatint

Gene Kloss

(1903–1996, American)

Printed by the artist. Kloss split her time between Berkeley, CA and Taos, NM at the time this print was made. She lived for about five years near Delta, CO, in the late 1960s.

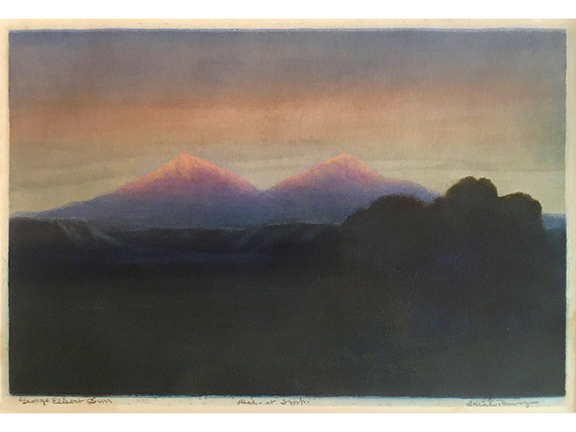

between 1906–1924

etching with aquatint, trial proof

George Elbert Burr

(1859–1939, American)

Printed by the artist in his Denver studio, where he lived and worked from 1906 to 1924.

1954

engraving, 14/25

Wendell “Bud” Black

(1919–1972, American)

Posthumous print by Black’s estate and former student Berkley Chappell at his Corvallis, OR studio. Black taught printmaking at the University of Colorado, Boulder from 1948 to 1972.

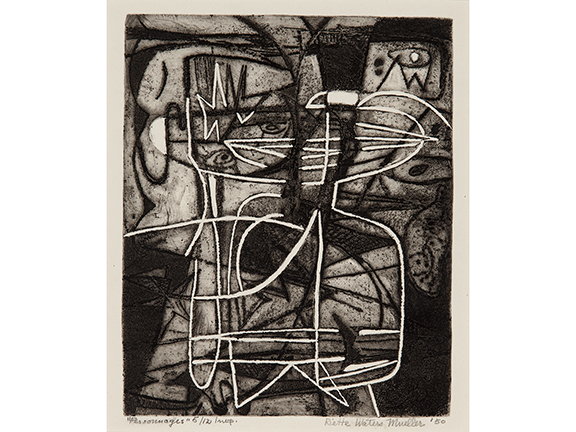

1950

etching, 5/12

Henrietta Waters Mueller

(1915–2009, American)

Unknown printer. She was living in Laramie at the time, where she was studying and teaching part time at the University of Wyoming. She moved to Boulder, CO, in the 1980s, where she lived until her death.

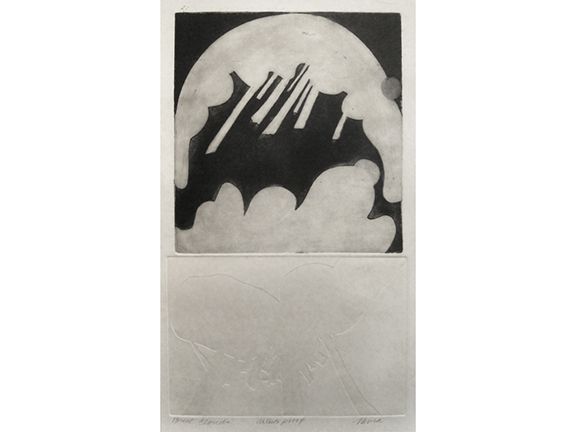

1969

etching with embossing, Artist’s Proof

Diana Vavra

(1938–2007, American)

Printed by the artist at the University of Colorado, Boulder; she received her MFA in Printmaking and Drawing there in 1970.

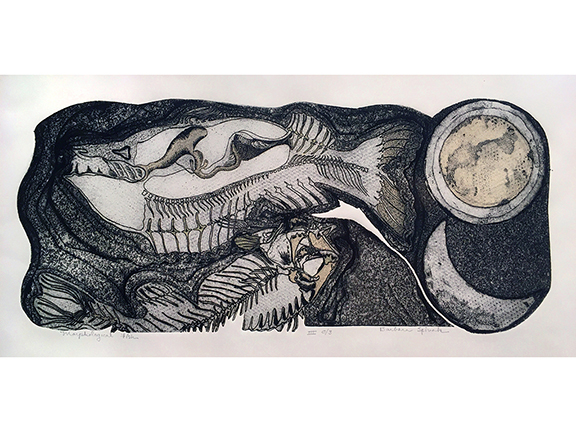

1973

hand-colored etching

Barbara Spivak

(b. 1926, American)

Printed and colored by the artist in her Denver Studio.

Gift of Barbara and Daniel Spivak

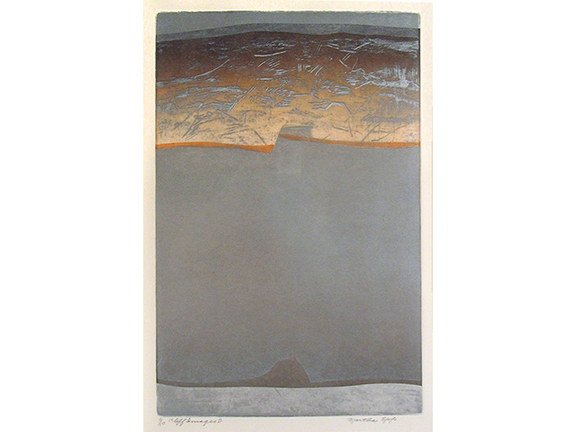

1980s

Etching with aquatint, 1/10

Martha Epp

(1907–1995, American)

Probably printed by the artist in Denver. Epp taught and was chair of the Art Department at Denver’s North High School from 1948 to 1972.

2011

zinc plate etching with chine collé

Mark Lunning

(b. 1961, American)

Printed by the artist at Open Press, Ltd., his gallery and printmaking studio in Denver, which he moved to Sterling, CO, in 2018.

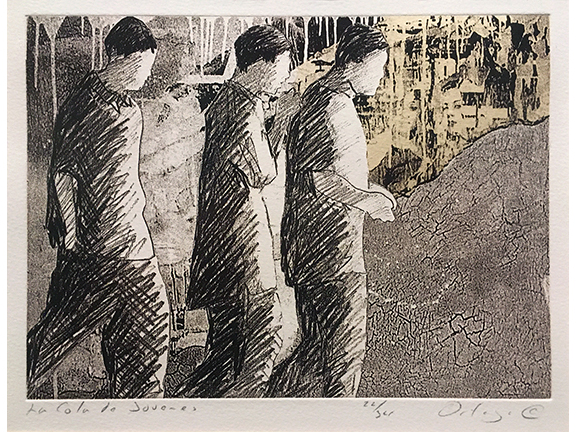

2005

polymer plate etching, 22/34

Tony Ortega

(b. 1958, American)

Printed by Mark Lunning at Open Press, Ltd., in Denver, which moved to Sterling, CO, in 2018.

Gift of Mark Lunning

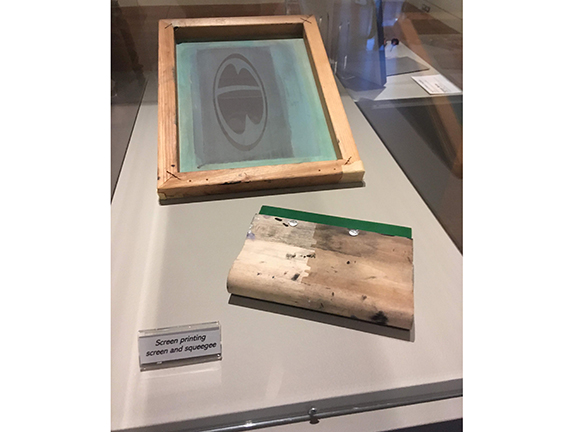

Screen Printing

Screen printing, referred to as Serigraphy in fine art printing, is a process of forcing ink through a screen mesh onto paper. Screens were originally made from silk, which is why the process is sometimes called silk screening. Today they are generally made from synthetic fabrics like polyester or nylon.

To make a screen print, a screen is stretched over a frame, given a light-sensitive coating and a transparency with a positive image of the artwork is placed against it. The coating hardens when exposed to light, while the areas blocked from the light are washed out with water, making openings in the screen for ink to pass through. The screen is then placed above the paper and ink is pushed through the openings with a rubber squeegee. Typically a different screen is used for each color in the print.

Screen fabrics are available in a variety of mesh sizes, which affects the amount of ink passing through the screen. The printer can choose a larger screen opening, which is good for a heavy application of ink as seen in the bold, blocky shapes of Roland Detre’s Indian Corn. A finer mesh can produce detail as in William Sanderson’s City of the Damned, or the thin, precise lines and smooth curves of the Dave Yust print, all included in this exhibition.

1949

serigraph

William Sanderson

(1905–1990, American, b. Latvia)

Unknown printer. Adapted from a 1946 painting by Sanderson owned by the Denver Art Museum, who offered this print as a membership gift in 1949.

Gift of Lucile Miller

1961

serigraph, 1/10

Eva “Eo” Kirchner

(1901–1991, American)

Printed by the artist in her Denver studio.

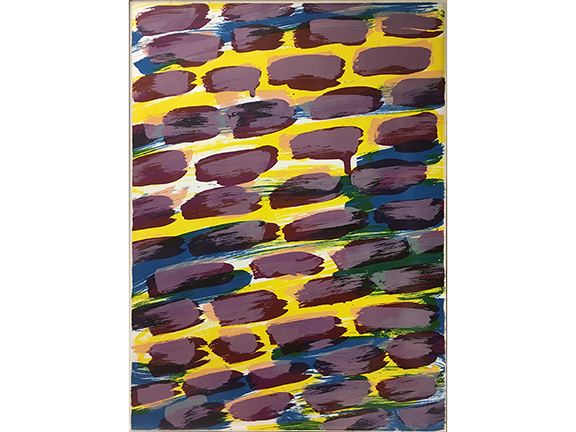

c. 1955

serigraph

Roland Detre

(1903–2001, American, b. Hungary)

Printed by the artist in his Denver studio.

early 1960s

serigraph, 1/6

Carley Warren

(b. 1931, American)

Printed by the artist at the Emily Griffith Opportunity School, Denver, with instructor Walt Green.

Gift of the artist

(Change in Scale #79)

1975

serigraph, 15/100

Dave Yust

(b. 1939, American)

Printed by Fred Jurado and sons at Fred Jurado Graphics, Denver.

Gift of Marlene Chambers and Family

1986

serigraph, Artist’s Proof

Reed Weimer

(b. 1957, American)

Printed by Mark Lunning at Open Press, Ltd., in Denver, which moved to Sterling, CO, in 2018.

To explore other virtual content from Kirkland Museum, please visit our Virtual Exhibitions Page.