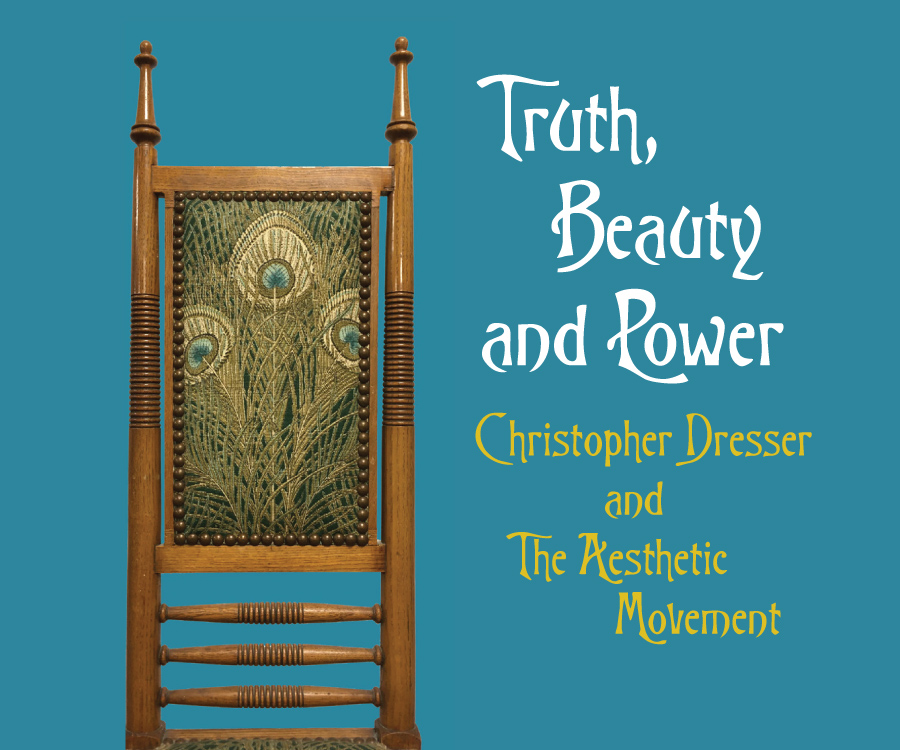

August 27, 2021–January 2, 2022

Presented by Deputy Curator Christopher Herron, chosen from the collection assembled by Founding Director & Curator Hugh Grant. Co-curated by Collections & Research Manager Becca Goodrum and Director of Interpretation Maya Wright.

Learn more about this lesser-known design movement through an exploration of common motifs used in designs from the Aesthetic Movement (c. 1865–1900) and the influence of British designer Christopher Dresser (1834–1904).

Special exhibitions are included with admission and do not require a separate ticket.

Virtual Lecture

Click the link below to watch a tour of Kirkland Museum including this exhibition, as well as a virtual lecture on the Dresser Discovery, presented as part of Join US Dresser Fest 21, a day of talks about Dr. Christopher Dresser and his work on September 18, 2021.

Setting the Stage for Design Reform

The industrial revolution began in Britain in the late 1800s. Manufacturers could suddenly produce objects very quickly. But that speed didn’t always come with much intention to the design, and especially the decoration or ornament, as it was called. By 1837, when Victoria became Queen, citizens had noticed the damage machine-production was doing to societal conditions and to the quality of goods. There was an economic need for change, as the manufactured goods were of poor quality.

This scenario led to a call for design reform. The Government School of Design was founded the same year (1837), with the goal of using industrial methods to make goods that were functional, high quality and good design.

Foundations of Kirkland Museum’s Collection

Kirkland Museum of Fine & Decorative Art has three collections, totaling over 30,000 works with approximately 4,400 pieces on view at any time. Nearly all of the artwork and objects at the Museum were collected by Hugh Grant and Merle Chambers. For the International Decorative Art collection, Founding Director & Curator Hugh Grant chose to begin with the Arts & Crafts Movement and Aesthetic Movement, both initially British design reform movements that in many senses signal the beginning of modernism–clean lines, less decoration and new materials made possible by machine production and increased global trade. Grant’s keen eye has led him to choose exceptional Arts & Crafts and Aesthetic Movement works for the collection, as well as recognizing and celebrating the importance of Christopher Dresser, whose work is always on view at Kirkland Museum.

This exhibition has been a treat to put together and serves as a celebration of the design reformers that set the stage for the decorative art movements that came after, also on view at Kirkland Museum. Through a carefully-chosen set of objects, all from Kirkland Museum’s collection and many newly-acquired or not usually on view, we invite you to look deeply at the foundations of our decorative art collection.

“Art for Art’s Sake”

The Aesthetic Movement began in England about 1865. Unlike proponents of the Arts & Crafts Movement, members of the Aesthetic Movement believed that art did not have to convey moral messages. They focused instead on the idea of a cult of beauty and believed art should provide pleasure.

Aesthetes, as followers of the movement came to call themselves, improved the artistry and cohesiveness of many aspects of society including art, literature, philosophy, interior design and the focus of this exhibition, decorative art. The word aesthetic means, “concerned with beauty or the appreciation of beauty.” Life, they asserted, should emulate art, rather than the other way around. These reformers ushered in modern ideas that defined the next century of design.

“Truth, Beauty, Power”

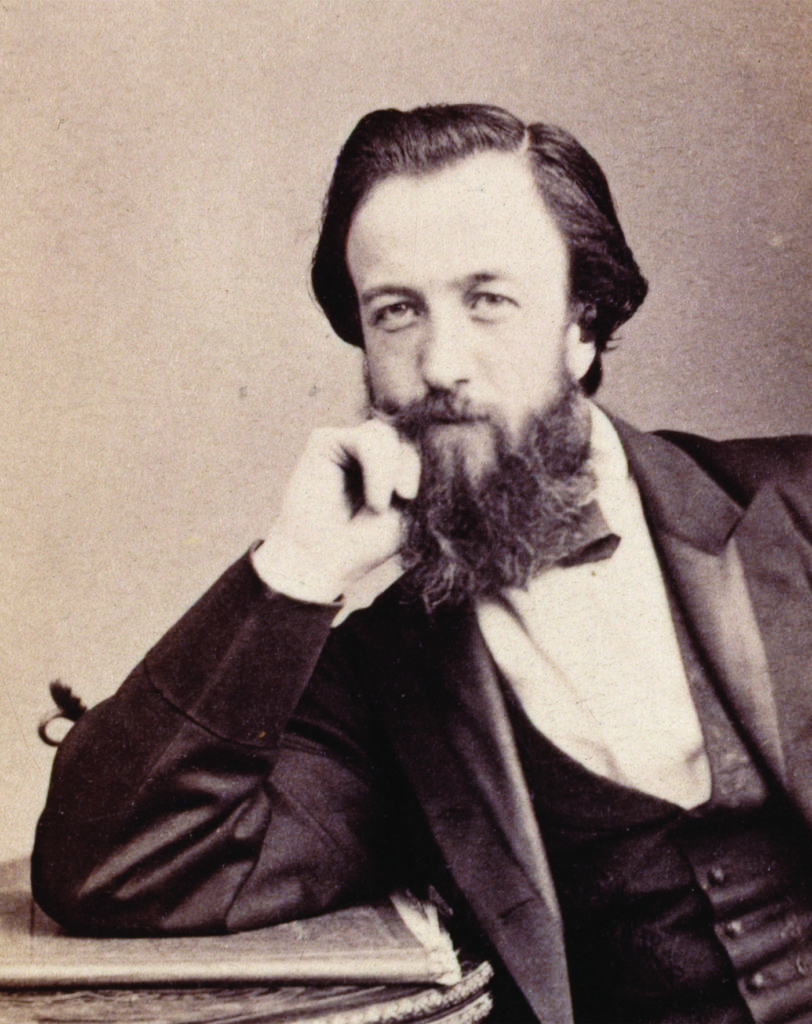

British designer Christopher Dresser (1834–1904) did not consider himself an aesthete, but his writings and teachings, as well as his own prolific designs, set the stage for a true shift away from earlier Victorian style and are emblematic of this era. This exhibition highlights Dresser’s work alongside pieces by other designers and companies that followed his design principles.

“Truth, Beauty, Power” was Dresser’s motto, painted on the door of his studio. It was important to Dresser to honor his materials and imbue the object with beauty using his knowledge of good design. The maker and work derived power through transforming a simple material into something attractive. He took the idea of truth very seriously, feeling that a two-dimensional surface should only have two-dimensional decoration.

In their own words…

Dr. Christopher Dresser vs.

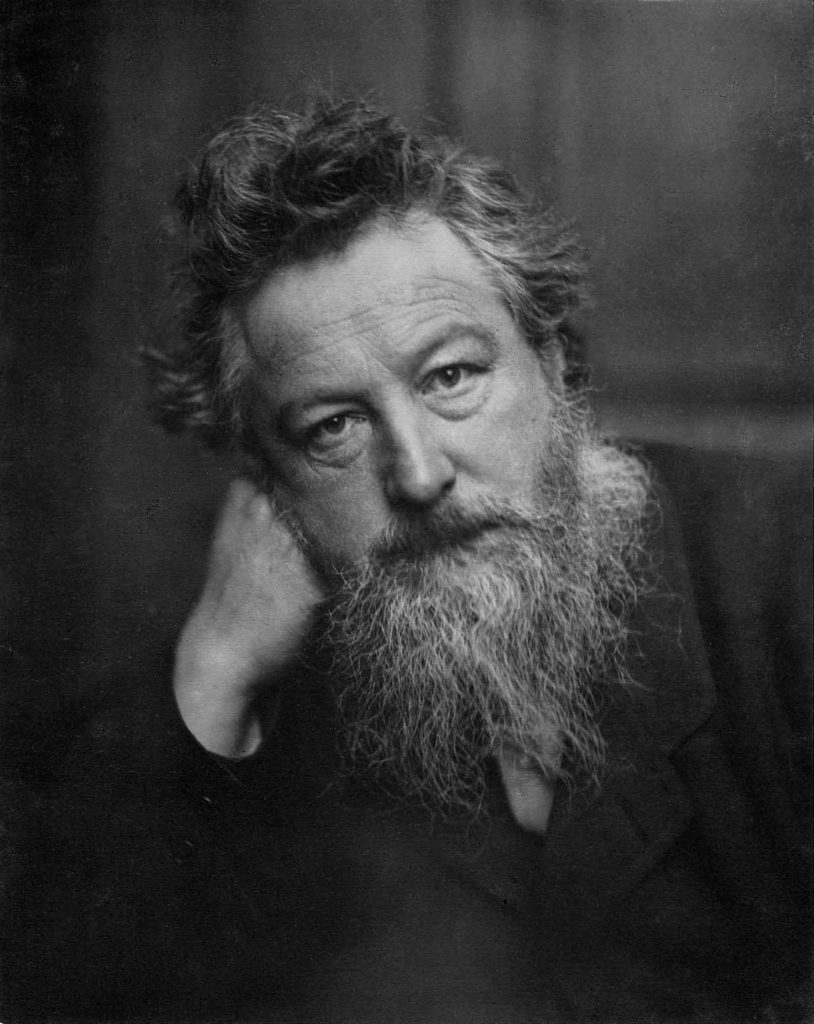

William Morris

“Many who cover their walls with costly paintings have scarcely an object in their houses besides these which has any art merit…Surely persons whose houses are thus furnished have bit little real love of the beautiful; he who admires what is pleasant in form and lovely in colour would regard the beauty of each object around him and the tout ensemble.”

Dr. Christopher Dresser

If you want a golden rule that will fit everybody, this is it: Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful."

William Morris

There can be no morality or immorality in art, the utterance of truth or of falsehood; and by his art the ornamentist may exalt or debase a nation.”

Dr. Christopher Dresser

Apart from my desire to produce beautiful things, the leading passion of my life has been and is hatred of modern civilization."

William Morris

My object in writing this work [Principles of Decorative Design] has been that of aiding in the art-education of those who seek a knowledge of ornament as applied to our industrial manufactures.”

Dr. Christopher Dresser

Furthermore, if any of these things make any claim to be considered works of art, they must show obvious traces of the hand of man guided directly by his brain, without more interposition of machines than is absolutely necessary to the nature of the work done.”

William Morris

Christopher Dresser Discovery

Kirkland Museum announces new chair attribution!

In preparation for the upcoming exhibition Truth, Beauty and Power: Christopher Dresser and The Aesthetic Movement, Museum curatorial staff, working with international experts, uncovered new research attributing the design of a beautiful five-legged chair to famous British designer Christopher Dresser. The chair has been on view with Arts & Crafts and Aesthetic Movement designs at Kirkland Museum since May 2018, with no designer identified. Kirkland Museum is likely the first museum in the United States to display this chair with this attribution.

The chair and the story of the attribution are a central part of the exhibition.

Research in preparation for the exhibition led staff to contact experts at the Dorman Memorial Museum in Middlesbrough, UK, which has the world’s largest public collection of works designed by Christopher Dresser. Dorman Museum then reached out to Harry Lyons, Dresser expert and author of Christopher Dresser: The People’s Designer 1834–1904.

“After preliminary research, I started making the connection to Dresser, and, after working with Dorman Museum and Mr. Lyons (both based in the UK), I was thrilled to find a compelling link between Dresser and our chair,” states Collections & Research Manager Becca Goodrum. “Dresser and his role in the Aesthetic Movement are an important early foundation of our decorative art collection. The discovery of this attribution further elevates the importance of our chair and enhances our wonderful collection even more.”

“In conjunction with our exhibition, we are delighted to announce that per Harry Lyons and Dorman Museum, we believe this chair was designed by Christopher Dresser,” says Associate Museum Director Renée Albiston. “The chair was always intriguing, lovely and extraordinarily good design, only enhanced by this connection to one of the central designers of the era.”

There is no reason whatever why a chair should have four legs. If three would be better, or five, or any other number, let us use what would be best."

Christopher Dresser, 1873

Knowing Dresser’s feeling about chair legs and the timing of Dresser’s work, Mr. Lyons believes the Kirkland Museum chair itself, as well as the upholstery (added later to the chair), were designed by Dresser, though he notes no definitive proof has been found about this chair specifically.

Themes

In addition to the five-legged chair, this exhibition uses objects from Kirkland Museum’s collection to illustrate four themes common to Dresser and the Aesthetic Movement.

Japonisme

Color

Animalia

Art Botany